(Image courtesy: Kanarinka)

We are all familiar with the phrase ‘Data is the new oil’. And so it is, says Catherine D’Ignazio, co-author of Data Feminism, an intersectional feminist (i.e., where we stand on different dimensions in society, such as class, caste, gender identity, disability status, determines our privileges and marginalisations) look at today’s data-driven world. D’Ignazio doesn’t simply bring up the phrase to underline just how much businesses and governments depend on data, she digs deeper. Like oil, data is extracted, processed, produced and sold. Like oil, data can become concentrated in the hands of a privileged few unless we strive to democratise it. Like oil, data is a source of power.

I find discussions around data very interesting – from ensuring privacy, ownership, distribution of power, access to analysis, projections and what have you – there’s something new to discover every day. When I got my hands on Catherine D’Ignazio and Lauren Klein’s Data Feminism, I couldn’t wait to explore the world of data through the lens of intersectional feminism. I find the lens a revealing one. It highlights the ‘ands’ in our identities. And, because these ‘ands’ bring us a variety of advantages and disadvantages in different contexts, intersectionality becomes a guidepost in reflecting on our location in society, the privileges we have and the vulnerabilities we face.

While Data Feminism deeply examines power in data – data science by and for whom – what I found most interesting is the possibilities it opens up in using data for good. It is a call to action to reimagine our data narrative – to understand social hierarchies and figure out ways to subvert them. Data Feminism pays attention to communities that carry the most baggage, such as women, people of colour and immigrants, queer folk, and asks: How can we create an intersectional and inclusive data narrative? If data is the new oil, who is gaining from it and who is being left out? Can data topple unequal power structures and empower users instead?

D’Ignazio and Klein urge us to imagine a better future for all by keeping us rooted in an unequal past. This way, they don’t just tell us things, they illustrate what they know. They let us – the users – see and sense what is working and what isn’t in today’s data landscape.

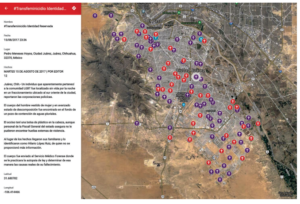

We see a map of femicides in Mexico, crowdsourced from the news and citizen reports. It has been created by María Salguero to plug the gaps in data collection and empower citizens to solve the problem of femicide. Salguero says, “This map seeks to make visible the sites where they are killing us, to find patterns, to bolster arguments about the problem, to geo-reference aid, to promote prevention of femicides.”

We see a map of femicides in Mexico, crowdsourced from the news and citizen reports. It has been created by María Salguero to plug the gaps in data collection and empower citizens to solve the problem of femicide. Salguero says, “This map seeks to make visible the sites where they are killing us, to find patterns, to bolster arguments about the problem, to geo-reference aid, to promote prevention of femicides.”

We see blueprints of Irth (Birth but without the “B for bias”), an app built to remove racism from maternal healthcare. Users, mostly people of colour and/or black women, upload reviews of the care they received at a hospital to enable other women to have safer and empowered experiences. Irth collates these experiences and uses the data to push for longer-term change in the healthcare system.

We see blueprints of Irth (Birth but without the “B for bias”), an app built to remove racism from maternal healthcare. Users, mostly people of colour and/or black women, upload reviews of the care they received at a hospital to enable other women to have safer and empowered experiences. Irth collates these experiences and uses the data to push for longer-term change in the healthcare system.

Paying tribute, we see a 2017 map of Canada called ‘Coming Home to Indigenous Place Names in Canada’. In stark difference, we see a 1930s Residential Security Map of Detroit which gives insight into racial segregation at the time and how racist policies of yore live on in urban planning of the present.

We see examples of how data can be used in service of society and how it can make social inequalities deeper. D’Ignazio and Klein tell us that to keep a check on the latter, Data Ethics came into being. However, they call Data Ethics a “Band-Aid” and are more interested in Data Justice. Data Ethics tries to smoothen the edges that may lead to unfair and biased practices, not decentralise power. Data Justice, on the other hand, goes one step further. It acknowledges historical and existing inequalities and can actively challenge power structures. It can create sustainable change.

It is undeniable that we are living in the age of data. I believe we need an intersectional feminist lens to think about and design for empowering communities to see, sense and solve the problems they face. We need to think like the blue dot of GPS: users at the centre and the world unfolding around what they need, where they are going and what the road ahead looks like. At Societal Thinking, we call this the Blue Pin Moment. Would you like to find yours?